Java Concurrency 101

Published:

This article provides understanding of Java Concurrency concepts, including threads, ExecutorService, synchronization, concurrent collections, threading problems, locks, conditions, semaphores, volatile variables, happens-before relationships, and barrier synchronization.

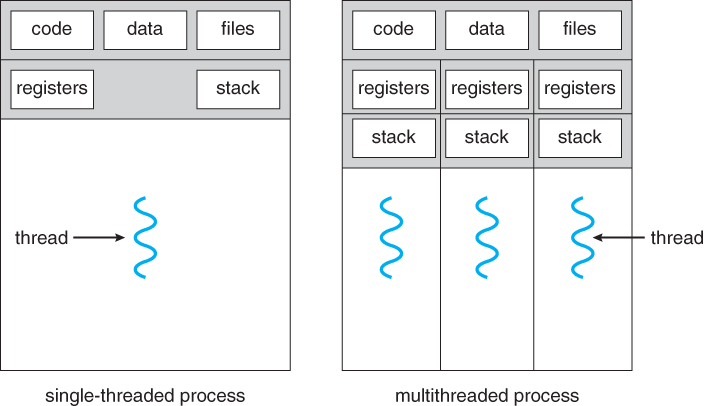

1. Introducing threads

Some definitions

- A thread is the smallest unit of execution that can be scheduled by the operating system.

- A process = group of threads that execute in the same, shared environment.

Threads in the same process share the same memory space and can communicate directly with one another.

- A system thread is created by the JVM and runs in the background of the application. ex: GC thread

- A user-defined thread is one created by the application to accomplish a specific task.

- A daemon thread are designed for tasks that run in the background and don’t prevent the JVM from exiting. ex: GC thread

Thread concurrency

- Operating systems use a thread scheduler to determine which threads should be currently executing. ex: round-robin scheduler

- If there are 10 available threads, they might each get 100 milliseconds in which to execute.

- When a thread’s allotted time is complete but the thread has not finished processing, a context switch occurs

- Thread can have priority

2. ExecutorService

- Obtain

ExecutorServiceinstance and send tasks to be processed

Single-thread executor:

- Results are guaranteed to be executed in the order in which they are added to the executor service

ExecutorService service = null;

try {

service = Executors.newSingleThreadExecutor();

service.execute(() -> System.out.println("Printing zoo inventory"));

} finally {

if(service != null) service.shutdown();

}

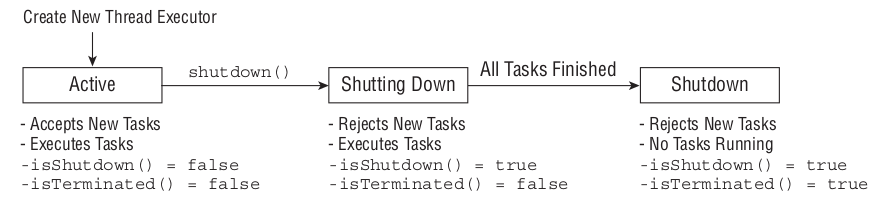

ExecutorService life cycle

- Note:

shutdown()not actually stop any tasks having already been submittedshutdownNow()attempts to stop all running tasks -> returnList<Runnable>of tasks were not started by the executor

ExecutorService methods

void execute(Runnable command)

Future<?> submit(Runnable task)

<T> Future<T> submit(Callable<T> task)

<T> List<Future<T>> invokeAll(Collection<? extends Callable<T>> tasks)

<T> T invokeAny(Collection<? extends Callable<T>> tasks)

- invokeAll() method will wait indefinitely until all tasks are complete, while the invokeAny() method will wait indefinitely until at least one task completes.

Waiting for all tasks to finish

- First shut down the thread executor using the

shutdown()method. - Then

awaitTermination()to waits the specified time to complete all tasks

ExecutorService service = null;

try {

service = Executors.newSingleThreadExecutor();

// Add tasks to the thread executor

...

} finally {

if(service != null) service.shutdown();

}

if(service != null) {

service.awaitTermination(1, TimeUnit.MINUTES);

// Check whether all tasks are finished

if (service.isTerminated())

System.out.println("All tasks finished");

else

System.out.println("At least one task is still running");

}

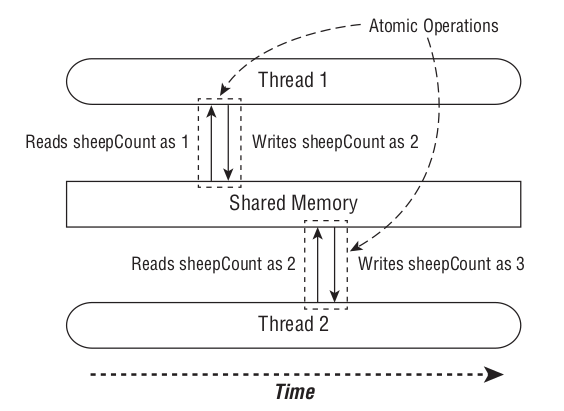

3. Synchronize Data access

- Synchronization is about

protecting data consistencyat the cost of performance

Atomic Classes

- Perform the read and write of the variable as a single operation, not allowing any other threads to access the variable during the operation.

- Any thread trying to access the variable while an atomic operation is in process will have to wait until the atomic operation on the variable is complete.

Atomic operation = read + write

Synchronize blocks

- A monitor is a structure that supports mutual exclusion or the property that at most one thread is executing a particular segment of code at a given time.

- In Java, any

Objectcan be used as a monitor, along with thesynchronizedkeyword

final Object lock = new Object();

private void incrementAndReport() {

synchronized(lock) { // If lock is available, A thread acquires the lock and preventing other threads from entering

// Work to be completed by one thread at a time

}

}

- We can add the synchronized modifier to any instance method to synchronize automatically on the object itself. For example, the following two method definitions are equivalent:

// synchronize on this

private void incrementAndReport() {

synchronized(this) {

System.out.print((++sheepCount)+" ");

}

}

private synchronized void incrementAndReport() {

System.out.print((++sheepCount)+" ");

}

- You can use static synchronization if you need to order thread access across all instances, rather than a single instance

// synchronize on class object

public static void printDaysWork() {

synchronized(SheepManager.class) {

System.out.print("Finished work");

}

}

public static synchronized void printDaysWork() {

System.out.print("Finished work");

}

4. Concurrent collections

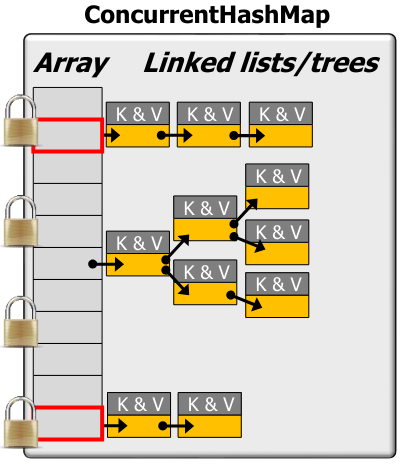

ConcurrentHashMap

- It uses a group of locks (16 in all), each guarding a subset of the hash table (segment lock)

- Its methods allow read/write operations with minimal locking

Internal:

- Array of buckets with locks on several entries. (segment lock)

- Each bucket can be a linked list or a binary tree if #Elements > threshold

- Behaviors

- R/W are concurrent if operate on different lists

- R/W to same list are optimized to avoid locking

- atomic add to head of list

- remove from list by setting data to null, rebuild list to skip null. Unreachable cells are GCed

- Entire map isn’t locked -> changes may not be visible immediately (there is no single lock that pushes all changes to all threads waiting)

Collections.synchronizedMap()

- a SynchronizedMap only uses a single lock -> slower

- Not scalable as ConcurrentHashMap

Java Blocking Queue

Adding to full queue / Get from empty queue can block client (with timeout)

- Consumer thread: wait for the queue to become non-empty when retrieving an element

- Producer thread: wait for space to become available when adding an element

Internally, many BlockingQueue implementations use

ReentrantLock&ConditionObjects

5. Threading problems

Liveness

- Liveness problems, then, are those in which the application becomes unresponsive or in some kind of “stuck” state

Deadlock

- Deadlock occurs when two or more threads are blocked forever, each waiting on the other.

- Example: Imagine that our zoo has two foxes: Foxy and Tails

- Foxy likes to eat first and then drink water, while Tails likes to drink water first and then eat. Furthermore, neither animal likes to share, and they will finish their meal only if they have exclusive access to both food and water\

- Foxy obtains the food and then moves to the other side of the environment to obtain the water. Unfortunately, Tails already drank the water and is waiting for the food to become available -> DEADLOCK

Starvation

- Starvation occurs when a single thread is perpetually denied access to a shared resource or lock.

- The thread is still active, but it is unable to complete its work as a result of other threads constantly taking the resource that they trying to access.

Livelock

- A livelock is similar to a deadlock, except that the states of the processes involved in the livelock constantly change with regard to one another, none progressing

- ex: Imagine that Foxy and Tails are both holding their food and water resources, respectively.

- They each realize that they cannot finish their meal in this state, so they both let go of their food and water, run to opposite side of the environment, and assetsk up the other resource. Now Foxy has the water, Tails has the food, and neither is able to finish their meal!

- Foxy and Tails are executing a form of failed deadlock recovery. Unfortunately, the lock and unlock process is cyclical, and the two foxes are conceptually deadlocked -> LIVELOCK

6. Lock framework

- The

Lockframework works in a similar manner to the synchronized code - Instead of being able to synchronize on any Object , we can only synchronize on an object that implements the Lock interface

- The

Lockframework ensures that once a thread has called the lock() method, all other threads that call lock() will wait until the thread that acquired the lock calls the unlock() method

// Implementation #1 with synchronization

Object object = new Object();

synchronized(object) {

System.out.print(" "+(++birdCount));

}

// Implementation #2 with a Lock

Lock lock = new ReentrantLock();

try {

lock.lock();

System.out.print(" "+(++birdCount));

} finally {

lock.unlock();

}

tryLock(long time, TimeUnit unit)

- The

tryLock()method will attempt to acquire a lock and immediately return a boolean result indicating whether or not the lock was obtained. - Unlike the

lock()method, it does not wait if another thread already holds the lock -> Can be used with timeout to avoid deadlock

Lock lock = new ReentrantLock();

if(lock.tryLock(10,TimeUnit.SECONDS)) {

try {

System.out.print(" "+(++birdCount));

} finally {

lock.unlock();

}

} else {

System.out.println("Unable to acquire lock, doing something else");

}

ReentrantLock()

- A simple monitor lock behaves most like the locks created by the synchronized keyword

One advantage to using the

Lockframework is that we can usetryLock()to avoid deadlockingunlock()method must be called the same number of times as thelock()method in order to release the lock

Fair Lock Management

- By default, when a

ReentrantLockreleases a lock, it then assigns it to a waiting thread at random if there are any, in the same manner as synchronized. -> Could lead to thread starvation

Lock lock = new ReentrantLock(true);

- When the

booleanvalue is set totrue, fairness is enabled and the longest waiting thread is guaranteed to obtain the lock the next time it is released

Read/Write Locks

- Read/Write locks are a type of lock that allows concurrent read access to an object but requires WRITE exclusive access.

- Lock

readLock()-> If there is no thread having write lock, then multiple threads can acquire read lock ~ multiple threads can read the data concurrently. Lock

writeLock()-> If no threads are writing or reading, only one thread at a moment can lock the lock for writing. Other threads have to wait until the lock gets released.- The idea is that many threads can be granted a lock to read the object, but a write object is special and can be granted only if no threads are holding any locks on the object

- ReadLock only waits when a write lock is granted.

public class ReadWriteLockExample {

private ReadWriteLock lock = new ReentrantReadWriteLock();

public void read() {

lock.readLock().lock();

try {

// perform read operations

} finally {

lock.readLock().unlock();

}

}

public void write() {

lock.writeLock().lock();

try {

// perform write operations

} finally {

lock.writeLock().unlock();

}

}

}

ReentrantReadWriteLock

- Java classic R/W lock

- Like the

ReentrantLockclass, it also accepts an optional fairness boolean parameter in its constructor

StampedLock

- Java 8++ implementation of R/W lock

Provides 3 locking modes

- Writing: Writing mode is “pessimistic” (assumes contention will occur), no other thread can acquire the lock while it’s held ~ a Write lock is “exclusive”

- Reading: Reading mode is “pessimistic” (assumes contention will occur), though other threads can acquire the lock for reading ~ a Read lock is “shared”

- Optimistic Reading: This reading mode is “optimistic” (assumes contention will not occur), so other threads can obtain the lock optimistically, i.e., the lock is “probabilistic”

- Locking mode can be converted to each other

- Compare to

ReentrantReadWriteLock:StampedLockis not reentrant ><ReentrantReadWriteLockis reentrantStampedLockhas optimistic reads, which is simpler/faster than read lock ofReentrantReadWriteLock- Reduced Blocking

ReentrantReadWriteLock: If there are many readers, writers can be starvedStampedLock: By using optimistic reads and a simpler read-write locking mechanism, Writers can invalidate optimistic read stamps efficiently.

7. Condition interface

- A

Lockreplaces the use of synchronized methods and statements, aConditionreplaces the use of the Object monitor methods. - Conditions (also known as condition queues or condition variables) provide a means for one thread to suspend execution (to “wait”) until notified by another thread that some state condition may now be true

- A Condition instance is bound to a lock using

lock.newCondition()method. - Use cases: java blocking collections

Condition.await()

-> Causes the current thread to wait until it is signalled or interrupted.

- The lock associated with this

Conditionis atomically released and the current thread becomes disabled for thread scheduling purposes and lies dormant until one of four things happens:- Some other thread invokes

signal()method for this Condition and the current thread happens to be chosen as the thread to be awakened - Some other thread invokes the

signalAll()method for this Condition - Some other thread interrupts the current thread

- Some other thread invokes

Condition.signal()

- Wakes up one waiting thread.

- One thread is chosen for waking up, this thread must re-acquire the lock before returning from

await() - Example:

// put() inserts an element into the queue. If the queue is full, it waits until there's space. After inserting an element, it signals any waiting threads that the queue is not empty.

// take() removes an element from the queue. If the queue is empty, it waits until there's an element. After removing an element, it signals any waiting threads that the queue is not full.

public class SimpleBlockingQueue<T> {

private Queue<T> queue = new LinkedList<>();

private int capacity;

private Lock lock = new ReentrantLock();

private Condition notFull = lock.newCondition();

private Condition notEmpty = lock.newCondition();

public SimpleBlockingQueue(int capacity) {

this.capacity = capacity;

}

public void put(T element) throws InterruptedException {

lock.lock();

try {

while(queue.size() == capacity) {

notFull.await();

}

queue.add(element);

notEmpty.signal();

} finally {

lock.unlock();

}

}

public T take() throws InterruptedException {

lock.lock();

try {

while(queue.isEmpty()) {

notEmpty.await();

}

T item = queue.remove();

notFull.signal();

return item;

} finally {

lock.unlock();

}

}

}

8. Semaphore

- A semaphore is conceptually an “object” that can be atomically incremented & decremented to control access to a shared resource

- It records a

count(“permits”) of how many units of a resource are available - It provides operations to adjust the permit count atomically as units are acquired or released

- Threads can wait (timed or blocking) until a unit of the resource is available

- When a thread is done with a resource the permit count is incremented atomically & another waiting thread can acquire it

Semaphore types

1. Counting semaphore

- Have # of permits defined by a counter (N)

- Negative: exactly -N threads queued waiting to acquire semaphore

- Zero = No waiting threads: an acquire operation will block the invoking thread until N is positive

- Positive = No waiting threads: an acquire will not block the invoking thread

2. Binary semaphore

Have only 2 states: acquired (0) & not acquired (1) ==> N = 0 N = 1

Java Semaphore

- A semaphore maintains a set of permits.

- Each

acquire()blocks if necessary until a permit is available, and then takes it. - Each

release()adds a permit, potentially releasing a blocking acquirer. - A thread that acquires a semaphore need not be the one that releases it

- Note: Semaphore not provide any guarantees about the synchronization (order) in which threads will access the shared resource, it only control the number of threads that can access code at the same time.

Methods

acquire()atomically obtains a permit from the semaphore, can be interruptedtryAcquire()obtains a permit if it’s available at invocation timerelease()atomically increments the permit count by 1 -> a thread waiting to acquire the semaphore can then proceed

Binary Semaphore vs Reentrant Lock (mutex)

- Mechanism

- Binary semaphore = signaling mechanism

- Reentrant lock = locking mechanism

- Ownership

- No thread is the owner of a binary semaphore. Any thread can signal (release) a semaphore, regardless of threads wait on (acquire) it.

- A lock (mutex) has ownership, the last thread that successfully locked a resource is the owner of a reentrant lock, Only thread that locks the mutex can unlock it

- Reentrant

- Binary semaphores are non-reentrant by nature -> same thread can’t re-acquire a critical section, else it will lead to a deadlock situation.

- A reentrant lock allows reentering a lock by the same thread multiple times.

9. Java Volatile Variables

- Ensure a variable is read from & written to main memory & not cached

- e.x: sharing a field between two threads

- Volatile ensures that changes to a variable are always consistent & visible to other threads atomically

- Reads & writes go directly to main memory (not registers/cache) to avoid read/write conflicts on Java fields storing shared mutable data

Volatile reads/writes cannot be reordered

- The Java compiler automatically transforms reads & writes on a volatile variable into atomic

acquire&releasepairs

- The Java compiler automatically transforms reads & writes on a volatile variable into atomic

- volatile write is visible to “happens-after” reads

- Note: incrementing

i++is not atomic

Piggybacking / volatile variable rule

- Anything prior to writing

truetoboolean vis visible to anything after readingboolean v. - => the

xvariable piggybacks on the memory visibility enforced byboolean v. Simply put, even though it’s not a volatile variable, it’s exhibiting a volatile behaviour.

public class VolatileExample {

int x = 0;

volatile boolean v = false;

public void writer() {

x = 42; // -> enfore volatile behavior

v = true;

}

public void reader() {

if (v == true) {

System.out.println(x);

}

}

}

10. Java “Happens-Before” Relationships

- In single thread, each action “happens-before” every action in that thread that occurs later in the program order

In multi-thread, actions in different threads can occur in different orders -> can cause problems without proper synchronization

- In computer system - “happens-before” guarantee that if one action “happens before” another action, the results must reflect that ordering

In Java, “happens-before” guarantee that an action performed by one thread is visible to another action in a different thread

- Cách các Thread chia sẻ dữ liệu với nhau (code theo để đảm bảo threadsafe):

- Program rule: Hành động trong cùng một thread happens-before các hành động khác trong cùng thread.

- Monitor lock rule: Hành động unlock happens-before trước các hành động lock trên cùng một monitor lock (synchronized). Tương tự cho interface Lock

- volatile variable rule : Hành động thay đổi một biến volatile happens-before trước các hành động đọc biến volatile. Tương tự cho Atomic

- Thread start rule : Hành động start() thread happens-before trước các hành động khác trong thread

- Thread terminate rule : Tất cả hành động của thead happens-before trước hành động thread.join(). Nghĩa là tất cả dữ liệu được threadB thay đổi sẽ được threadA nhìn thấy khi hàm threadB.join() trả lại.

- Transitivity rule : A happens before B & B happens before C => A happens before C

11. Java Barrier Synchronization

Introduction

- A barrier is a synchronizer that ensures thread(s) must stop at a certain point & cannot proceed until all other thread(s) reach this barrier

- Compare with other types of Java synchronizers

- Atomic operations: actions that happen effectively all at once or not at all (e.g: Atomic classes)

- Mutual exclusion synchronizers: allow concurrent access & updates to shared mutable data within critical sections (e.g: Lock)

- Coordination synchronizers: ensure that computations run properly order, time, conditions, … (e.g: ConditionObject)

3 types of Barrier:

- Entry barrier: keep concurrent computations from running untils object(s) are fully init

- e.g: Main thread spawns # of worker threads & then performs some timeconsuming initialization of data structures. After init workers can perform tasks.

- e.g 2: Tourists wait outside museum until it opens or until a tour is schedule to begin

Exit barrier: don’t let a thread continue until a group of concurrent threads have finished their processing

- e.g: The main thread waits on an exit barrier for all worker threads to finish

- e.g 2: The museum closes only after last group of tourists leave

- Cyclic barrier: a group of threads all wait for each other to reach a certain point before advancing to the next cycle

- e.g 2: Tour guide waits for all the tourists to finish exploring a room before continuing the tour in next room

CountDownLatch

- Allows one or more threads to wait on the completion of operations in other threads

- Supports 2: entry & exit barriers, but not cyclic barriers

- Well-suited for fixed-size, one-shot “entry” & “exit” barriers

- Simple APIs:

await()andcountDown()-> releases any threads blocked onawait()when count reaches 0

CyclicBarrier

- The

CyclicBarrierallows a group of threads to all wait for each other to reach a common barrier point. It is called cyclic because it can be re-used after the waiting threads are released. Supports 3: entry, exit, & cyclic barriers for a fixed # of threads

The

CyclicBarrieris initialized with a given count = number of threads it should wait for.- As threads reach the barrier point, they call

CyclicBarrier.await(), which puts the thread into a waiting state. - Once the specified number of threads have each called

await(), the barrier is considered broken and all waiting threads are released to continue execution.

- As threads reach the barrier point, they call

Compare

CountDownLatchvsCyclicBarrier:CountDownLatchfocuses on actions (entry + exit)- When 1 thread waits until N threads have completed an action

- 1 thread waits until an action has completed N times, irrespective of which thread(s) were responsible

CyclicBarrierfocuses on threads (entry + exit + cyclic)- When N threads wait for each other to reach a common process point

- Internally,

CyclicBarrieruse Lock + Condition + # parties +Runnable barrierActionwhen all parties arrive

public class CyclicBarrierExample {

public static void main(String[] args) {

final int totalThread = 5;

// Runnable - barrierAction ~ the command to execute when the barrier is tripped, or null if there is no action

CyclicBarrier barrier = new CyclicBarrier(totalThread, () -> System.out.println("All tasks are finished."));

ExecutorService executorService = Executors.newFixedThreadPool(totalThread);

for (int i = 0; i < totalThread; i++) {

executorService.execute(() -> {

System.out.println("Before barrier: " + Thread.currentThread().getName());

barrier.await(); // Block until all parties arrive & barrier resets

System.out.println("After barrier: " + Thread.currentThread().getName());

});

}

executorService.shutdown();

}

}

Phaser

- A more flexible, reusable, & dynamic barrier synchronizer that combines CyclicBarrier & CountDownLatch

- Allows a variable (or fixed) # of threads to wait for all operations performed in other threads to complete before proceeding

- Number of parties can vary dynamically

Supports 3: entry, exit, & cyclic barriers for a variable # of threads

Internally,

Phaserusesvolatile long state(4 bit fields)- Unarrived - the # of parties yet to hit barrier (bits 0-15)

- Parties - # of parties to wait for before advancing to the next phase (bits 16-31)

- Phase - the generation of the barrier (bits 32 - 62)

- Terminated - if barrier is terminated (bit 63 / sign)

- Compare to

CyclicBarrier:Phaserallows threads to dynamically register and deregister. This is useful in scenarios where the number of tasks or threads is not known in advance.Phasersupports multiple phases of computation. Once all threads have arrived at thePhaser, it advances to the next phase. This is useful in iterative algorithms where each iteration is a separate phase.- Flexiable arrival: A thread can wait for all parties to arrive or can just register its arrival using

arrive()and continue without waiting for others.

Leave a Comment